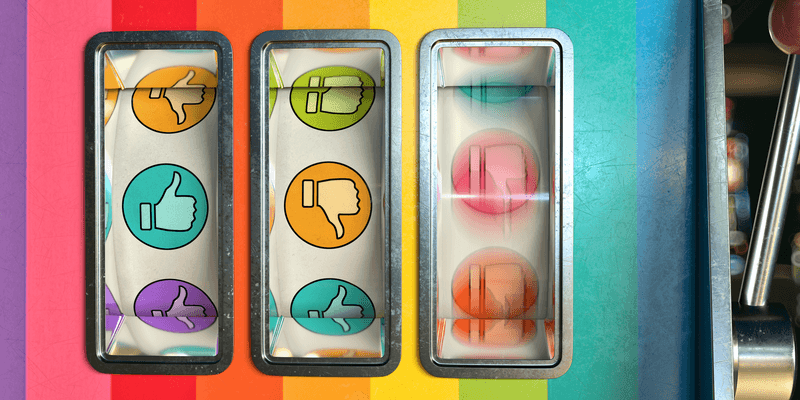

The Feedback Gamble

Being proactive can be risky if an employee is not up to speed

By Katleen De Stobbeleir

Professor of Leadership

In today’s dynamic workplace employees are expected to be proactive - seeking feedback, taking the initiative, selling ideas, taking charge, revising tasks and building social networks. But a new study shows that some employees may, in fact, pay a price for sticking their head above the parapet if they are not known to be top performers.

The research by Katleen de Stobbeleir, Susan Ashford and Mary Sully de Luque examined how an employee’s track record, their manager’s beliefs, and how often they ask for feedback will affect how supervisors weigh up their proactive behaviour.

While past research has focused on how proactivity can help individuals, teams and companies, this study, “Proactivity With Image in Mind: How Employee and Manager Characteristics Affect Evaluations of Proactive Behaviors”, suggests that it may not always be beneficial.

If feedback backfires, it can deter employees in the future, and this can limit the potential productivity gains to the company and ultimately a worker’s pay, performance and development opportunities.

ASKING THE BOSS: Pros and Cons

De Stobbeleir, Ashford and de Luque examine how seeking feedback affects the way a manager evaluates staff.

Seeking feedback is considered a positive thing by enabling employees to adapt and respond to changing goals and expectations and so improve their performance. But research suggests that managers interpret requests for feedback in different ways, and at the end of the day such evaluations will shape the nature of his or her relationship with a member of staff and ultimately that employee’s pay and prospects.

On the one hand, a manager may attribute a request for feedback to an employee’s commitment to improving his or her performance. A worker may want to know more about his or her responsibilities; to discover exactly what is expected of him; to perform better and learn etc. On the other hand, that manager may interpret it as an effort by an employee to manage perceptions others have of him or her. The worker may be trying to make a manager believe he or she is helpful; to look good; to obtain recognition or rewards etc.

The more a manager attributes requests for feedback to an effort to improve performance, the better that supervisor tends to evaluate the employee’s work. But if a manager thinks an employee is merely seeking to manage his or her image, this can taint their view of that employee’s contribution.

GOOD BEHAVIOUR: Performance Matters

Theory suggests that managers respond to cues when evaluating workers’ behaviour - particularly their performance record. Scholars have found that, of the staff who seek feedback, average workers are seen as less confident and competent than superior performers. Paradoxically, this means that those who stand to gain most from feedback may in turn be the most reluctant to ask for it because they fear how it will be evaluated.

The researchers predicted that managers are more likely to attribute an employee’s motive for seeking feedback to an effort to improve their performance if they are better workers, and more likely to attribute it to a desire to manage their image if they are average workers. However, a manager’s opinion will also depend on how often member of staff asks for feedback. Research has assumed that the more feedback people seek, the better – but some studies suggest requesting feedback often can be seen as dysfunctional.

The researchers predicted that if an employee seeks feedback frequently, it will strengthen the assumptions managers typically make about why an employee does so. Managers will be more likely to attribute requesting feedback often to an effort to improve performance if it comes from a better worker and, if it comes from an average worker, more likely to see it as an effort to manage his or her image.

PERSONALITY TYPES: What Managers Believe

The way in which a manager interprets why an employee wants feedback will also depend on that manager’s personality.

One important characteristic is a supervisor’s beliefs regarding the ability of staff and how capable they are of changing. Some managers believe people’s personal characteristics and abilities are largely fixed, while others think they can grow and develop. Managers who believe staff cannot change will not believe feedback will help them - so would not interpret a request for feedback as an effort to boost performance. By contrast, managers who believe staff can change and develop are more inclined to see the value of feedback to enhancing performance.

Given this, the researchers predicted that managers’ personal beliefs regarding ability will affect their assumptions when a worker seeks feedback, and such assumptions will be strengthened the more often a worker seeks feedback.

VIGNETTES: Research and Results

The researchers used an online survey of 319 current and former students from an MBA programme in the US to test their ideas. Respondents read a vignette that described a situation in which an employee seeks feedback and then assumed the role of his manager. The role-play varied the employee’s past performance and how often he asked for feedback.

The results demonstrated that:

- the performance record of the person seeking feedback affects the motive a manager attributes their desire for feedback to. A request for feedback by a good worker is seen much more as an effort to boost their performance than that of an average worker.

- however, managers do not use an employee’s performance record as a cue to decide whether or not a request for feedback is driven by a desire by that worker to manage his or her image.

- frequent requests for feedback do not affect the tendency of managers to see the feedback requests of better workers as an effort to enhance their performance and those of average workers to managing their image.

- the more inclined a manager is to believing workers cannot change, the more likely he or she will be to attribute frequent requests for feedback to an effort by an employee to manage his or her image.

- when a manager assumes that a request for feedback is an effort by a worker to manage his or her image, this can harm that manager’s opinion of the worker’s character and potential. Managers who assume a request for feedback is an effort by a worker to enhance his or her performance evaluated that employee’s character and potential much more positively.

IMPLICATIONS: Getting the best out of staff

The research reveals the potential risks of being proactive and paints a more nuanced picture of the forces can that affect productivity.

The results suggest that a worker’s performance record represents a powerful cue influencing how managers evaluate their requests for feedback. What seems to matter most is a worker’s track record: requests for feedback by better employees are interpreted as efforts to further enhance their performance, while requests by average worker are not. Nonetheless, managers do not necessarily believe the latter will be trying to manage his or her image, and nor is the way managers weigh up how often an employee seeks feedback strongly related to that worker’s record.

A key finding is that the effect of asking for feedback often will depend on a manager’s general beliefs about workers. Managers given to thinking staff do not generally change attribute frequent requests for feedback to an effort by an employee to boost his or her image. So the question of how often it is best to seek feedback will depend on characteristics of the manager and the quality of his or her relationship with a particular member of staff.

The Research Team’s Conclusions have Important Implications for the Workplace:

- Organizations need to ensure that if staff seek feedback their managers do not see this merely as an effort to boost their image. Companies might address this by training all staff about the value of feedback, especially those managers who believe workers are unlikely to change and so do not appreciate the full value of feedback. Training these managers to believe that staff can improve can enhance their willingness to coach subordinates, distinguish between good and bad performance, and help them see the benefits of feedback for those average workers who need it the most.

- Staff need to be cautious because seeking feedback can come at a price: paradoxically, employees need to have a sense of how they are perceived to be performing before approaching managers for feedback. Instead of seeking feedback directly, average workers need to employ more subtle strategies, such as asking colleagues and managers indirectly. It might also be wise to seek feedback from several managers, so that each is approached infrequently.

- It is important for employees to get inside their manager’s head: if their supervisor is inclined to believe that people cannot change, they will not see feedback as of any use and so, in these cases, asking for it may be counterproductive. It might be wiser for an average performer to seek feedback from managers who are more inclined to believe they can change for the better.

Related article

Katleen E. M. de Stobbeleir, Susan J. Ashford and Mary F. Sully de Luque. 2010. Proactivity With Image in Mind: How Employee and Manager Characteristics Affect Evaluations of Proactive Behaviors. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology Volume 83, Issue 2, pages 347–369

Get in touch!